It was a routine Pentagon announcement during a regular briefing the Friday before the president typically submits his annual defense budget request to Congress on the second Monday in March.

Since October 2023, “certain” Air Force F-35As have been operationally certified to carry the B61-12 thermonuclear gravity bomb, a spokesman for the Department of Defense’s (DOD’s) F-35 Joint Program Office told Pentagon beat writers.

While the revelation hasn’t drawn much interest from general news media in the United States, it has spurred extensive commentary within the defense-tech industry. And it is echoing loudly in Europe, most certainly within the Kremlin, where Russian President Vladimir Putin has been openly discussing the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

The F-35A nuclear certification and introduction of the B61-12 bomb are key components in a tactical nuclear weapons upgrade in Europe by NATO in response to Russian saber-rattling—and advances—in battlefield nuclear weapons.

While NATO’s U.S.-built F-16A/Bs and F-16C/Ds and UK-built PA-200 Tornadoes are also fighter jets authorized to carry nuclear weapons, the F-35A Lightning II is now the first “fifth-generation” stealth fighter to be “dual-capable” of carrying conventional and nuclear weapons, according to the Pentagon.

The F-35A will soon be among NATO’s primary attack-strike jets. Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey are all stocking their air forces with F-35s, with Germany explicitly doing so because it would be nuclear-capable.

The March 8 announcement also confirmed the full-scale production of the B61-12 bomb. Their predecessors were housed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. According to some reports, they’ve been replacing them with new bombs since December 2022.

October 2023’s nuclear certification was two months earlier than the January 2024 deadline the Pentagon set. Although only publicly acknowledged by the United States on March 8, Dutch military officials wrote in a November 2023 post on social media platform X that their F-35As had achieved “initial certification” to carry nuclear weapons.

Since Pentagon policy prohibits the release of information about NATO partner military capacities, the announcement only addressed “certain” U.S. Air Force F-35As in Europe, with the U.S. fighter wing at Lakenheath in the UK likely among those upgrading.

“A lot of this is just information warfare, SOP [standard operating procedure] and optics that we got F-35As and allies who have F-35As in Europe,” retired Army Col. John Mills told The Epoch Times.

Mr. Mills, a 33-year Army veteran and former director for cybersecurity policy, strategy, and international affairs under the secretary of defense, said the F-35A “has always been about Europe.”

“The message is that the F-35s are now there, and they are nuclear certified, and B61-12s are in storage ready to go, ready to be used, if necessary, out of Lakenheath,” he said.

“Of course,” he said. “He’s the target.”

“The F-35 has pretty good range for a single-engine fighter. It is stealth, and so you could obviously get closer to Russian air space before being effectively targeted than you could, let’s say, with an F-15,” he said, noting that with 600 to 700 F-35s in U.S. and allied air forces, “at any given time, some of them are probably capable of flying.”

Mr. Fredenburg admits: “I’m not a huge fan of the F-35.”

So little so that for those who have followed the aircraft’s checkered development for the past 30 years, he had to quantify how truly significant the F-35A certification is.

“I don’t want to say it’s insignificant. It does, I think, potentially create some more instability because nobody else has many stealth fighters,” he told The Epoch Times.

A Long, Haunted History

“First of all, you have to look at the history. From the very beginning, it was doomed. It was too heavy. There’s no way you can make a reliable engine powerful enough and light enough to fly a plane that big. The plane is the largest single-engine plane in the world.”

When first envisioned in the early 1990s, the F-35 was touted by Lockheed Martin as an all-purpose, next-generation stealth joint-force single-engine fighter that would replace up to 16 different types of warcraft, including the Navy’s F-14, the Air Force’s F-16, and the Marine Corps’ Harrier jump jets.

That was nearly two generations ago.

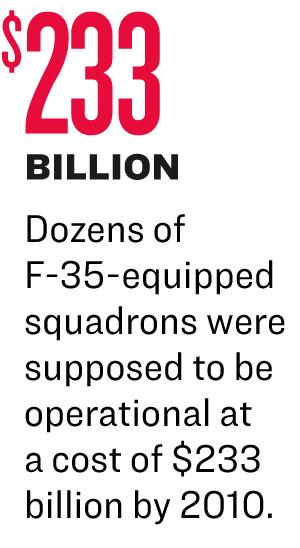

Design began in 1994. After a series of delays, dozens of F-35-equipped squadrons were supposed to be operational at a cost of $233 billion by 2010.

“It didn’t even come close to that,” Mr. Mills said.

By 2016, the project’s cost had doubled. It remains more than a decade behind schedule and billions over budget with mixed results, some say.

“What they did is, you know how you ‘soup up’ your car? Put nitrate in it or something like that?” Mr. Fredenburg said. “You might be able to get it around a few times before it blows up, but that’s what they did here.

“They ‘souped up’ the F-35 engine and made it super, super hot to get the horsepower, that thrust, and there’s no way that engine was going to be durable.

“So it’s got an engine that can’t do the job. It won’t be reliable ever. Ever.”

Mr. Mills said the jet poses different problems than other aircraft because its airframe is made mostly of epoxy plastics, which emit toxic smoke if on fire, and it is dramatically louder than any other fighter.

“So the thing’s heavy,” Mr. Fredenburg said. “It’s not very aerodynamic. It’s just not a good airframe. You could put all this electronic stuff on it and ... all the software-enabled features, but it’s just never going to be a good plane. It’s always going to have heating issues.

“I mean, they’re not even certified for full-rate production yet ... and it’s just mind-boggling how much that thing costs.”

The Government Accountability Office reported in April 2023 that since 2004, F-35 development has cost more than $1.7 trillion, and that as of 2018, they cost about $44,000 per hour on average to operate, more than twice the cost of operating the Navy’s F/A-18E/F Super Hornets.

The $1.7 trillion figure is what it will cost the DOD to develop, buy, operate, and sustain these aircraft, with the latest publicly available F-35 development costs tabbed at more than $79 billion in December 2022.

The New York Times editorial board, among others during the past decade, has called the F-35 a “boondoggle” and “the most expensive weapons system in the history of mankind.”

It didn’t help when, in August 2023, the Pentagon paused F-35 deliveries because it discovered that a Chinese-made part was used in production.

In addition to a jet tail section that limits how long the F-35 can stay in supersonic flight, the aircraft has been plagued by flaws in its stealth coating, difficulty finding spare parts for their $12 million engines, and a communications system some believe is vulnerable to cyberattack.

Nevertheless, Lockheed Martin maintains that the lessons learned over the past three decades have resulted in a fighter that can perform a range of missions for decades to come.

Navy to Follow Suit

While deploying nuclear-capable Air Force F-35As is largely aimed at bolstering NATO in Europe and convincing Russia that the use of a battlefield nuclear weapon guarantees a return volley—a tactical mutual assured destruction—Mr. Fredenburg said it also carries significance for China, which is also working on a nuclear-capable stealth fighter.The Pentagon announcement that “all F-35As in the Air Force inventory are expected to be in a nuclear-certified configuration in the future” essentially heralded, he said, that “the F-35 is the first stealth fighter to carry a nuclear weapon, and we beat the Chinese to it.”

The DOD did not mention the Marine Corps’ F-35B version, which has a vertical liftoff capacity, or the Navy’s F-35C model, which is fortified for carrier operations, but both are expected to have their F-35s nuclear-capable—and to do so without public notice.

“It would make sense” for the Navy to do so because dealing with China is its primary mission, Mr. Fredenburg said.

Mr. Mills wishes the Pentagon had referenced the Pacific.

“What does it mean for the Pacific? I don’t know yet,” he said. “I also don’t know why this administration refuses to do something that will be meaningful” in countering China in the western Pacific.”

Mr. Mills said the Navy had to overcome Biden administration objections in order to “reintroduce” nuclear warheads on Tomahawk missiles.

Like the F-35As, the B61-12 bomb has a long production history. It is at least the sixth iteration of a relatively low-yield, semi-maneuverable, almost-glide weapon that began under the Obama administration.

The first B61-12 rolled out in November 2021, with production scheduled through the end of fiscal year 2025 at a cost of $9.6 billion.

The Biden administration announced in October 2023 that it would develop the B61-13, which at a 360-kiloton blast equivalent would be seven times more powerful than the 50-kiloton B61-12.

The B61-12 is “lower yield, but the idea is to trade off with accuracy; if you can hit closer to the target, you don’t need as powerful a bomb to take out the target,” Mr. Fredenburg said.

The Air Force maintains that the B61-12 has the capacity to glide the last 50 miles to a target after being launched from an F-35A.

“So at least you can get closer and have a standoff range,” Mr. Fredenburg said. “In other words, from the time you drop it, it will glide another 50 miles.”

Mr. Mills thinks the Pentagon is overplaying that capacity.

“It doesn’t have the capacity to glide,” he said, noting that he doesn’t know if the claim is an intentional exaggeration of the B61-12’s “glide capability.”

“I have never seen the B61-12 having wings for glide capability. It has a tail. It has fins. That’s two different things,” he said.

“We can quibble and argue that [fins] give it a little bit of a glide capability, but not like a wingtip. So those are totally different engineering components. I think they’re being clever with that.”

The B61-12 is as much “a free-fall nuclear bomb” as its predecessors, and “you still effectively have to fly over, come very close, to the target. Which means your aircraft and pilot are at risk,” Mr. Mills said.

Mr. Fredenburg agreed, somewhat.

“It doesn’t have wings, but it’s got that thrust, that momentum for high altitude. They may have 15 miles of extra range, so that, plus coming in stealthily, does make it more of a threat,” he said.

Both agreed that the 30-year saga of the F-35, decades behind schedule, billions over budget, and never-ending complexities, is not the exception to the rule at the Pentagon but the way business is done and has been done for more than 70 years.

“It’s not just this. This is just prototypical of all the other problems. We just are not making things fast enough,” Mr. Mills said.

“It’s not just that it’s the biggest defense program ever in the history of the world, even with inflation adjusted, it’s about opportunity cost,” Mr. Fredenburg said, claiming that the time, effort, and money put into the F-35 could have been better spent on other military programs.

“I’m a pro-defense guy, a peace-through-strength kind of guy. I believe in the military, but I think there’s no other military in the world that’s getting less bang for their buck than we are.”