In 1624, exactly 400 years ago, the Dutch founded the colony of New Amsterdam within the colonial province of New Netherlands along the eastern seaboard of the American continent. After winning independence from Spain in the 1580s, the Dutch Republic (also known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands) experienced its financial “golden age” during the 17th century, becoming the financial capital of the world.

New Amster…York

Before the war broke out, New Amsterdam received a new governor, Petrus Stuyvesant, in 1647. The man with a wooden right leg had proven himself a successful leader for the Dutch Republic’s West India Company. When he arrived, he found New Amsterdam in disarray and quickly worked to organize and, literally, clean up the colony. A decade after the First Anglo-Dutch War ended, however, New Amsterdam would be faced with a direct English threat.

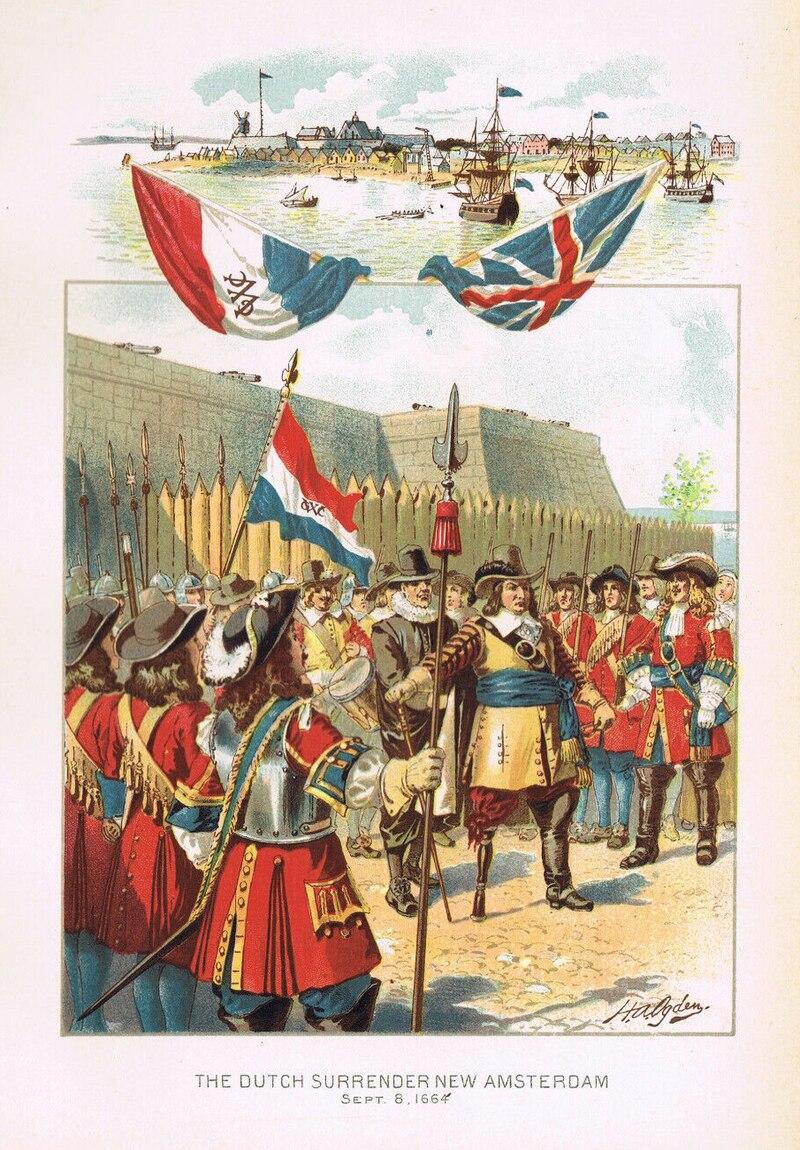

In 1664, four British ships with 450 soldiers, led by Richard Nicoll, who was commissioned by James, Duke of York, sailed to New Netherlands to lay claim to New Amsterdam. Upon their arrival on Aug. 18, 1664, they sent Stuyvesant a letter promising the Dutch colonists trading and immigration rights on the condition of surrender. Stuyvesant tore up the letter.

When the Dutch colonists got wind of his response, they quickly met with Stuyvesant, convinced him to reassemble the letter, and read it aloud. Upon hearing the contents and taking note of the ships and soldiers, the Dutch agreed to the terms of surrender on Aug. 27.

Fort Amsterdam was renamed Fort James and New Amsterdam was renamed New York. The Dutch colony had lasted 40 years.

Dutch Subversion

Over the next century, the New World became the center of imperial conflicts over the colonies. One of the most instrumental conflicts came as part of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), which involved the Austrians, British, French, Prussians, Russians, Spanish, and Swedes, and reached five continents. Among the five was the American continent’s French and Indian War, which pitted the British and French against each other. The former proved victorious, but at a hefty financial cost. During the overarching global conflict, however, Dutch trade enjoyed financial opportunities due to its neutrality.The Dutch and the British had maintained a peaceful relationship since its third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–74). That would change a century later with the outbreak of the American Revolution. Without official permission, Dutch merchants began supplying Americans with materiel, like gunpowder and cannonballs, in exchange for tobacco and other goods. The merchants utilized their colonies in St. Eustatius and Curaçao (both still Dutch islands in the Caribbean) as go-betweens.

When the American Revolution began, the British requested military support from the Dutch, citing treaties between the two nations. The government at The Hague, however, demurred, much to British chagrin. The Dutch’s undermining of the British in the colonies was subtle and consistent. While merchants continued to supply the patriot cause and The Hague refused to budge on assistance, the British saw the culmination of this subversion on Nov. 16, 1776, when the Dutch at St. Eustatius saluted the newly minted American “Grand Union” flag. It is considered the first time the U.S. flag was recognized. In response, during the summer of 1777, the British seized 54 Dutch ships.

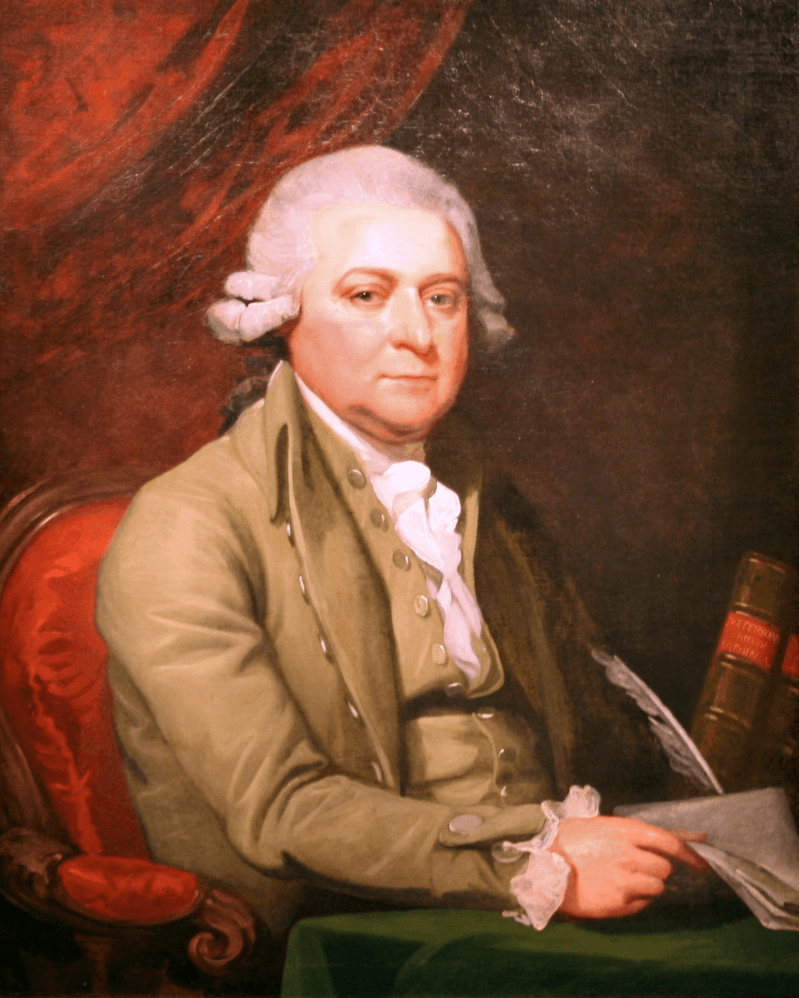

Fumbles by John Adams

In the rebelling colonies, John Adams was one of the leading figures in the Continental Congress. He had nominated George Washington in 1775 to be commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. In 1776, he had, along with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston, formulated the Declaration of Independence. And he proved one of the most influential political leaders in creating the new government.Toward the end of 1777, after the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga, the French decided to ally with the American patriots. On Feb. 6, 1778, the French, who were still bristling from the French and Indian War losses, signed the Treaty of Alliance. Adams was sent to help with formulating the treaty, but upon arrival was informed the pact had been signed. Irritated and humiliated, Adams returned home. Congress, however, had other plans for him. He was to return to Europe to negotiate a possible peace treaty with the British.

Lucky Dutch

Communications during the 18th century, however, traveled slowly, and Adams was unaware of his recall. He decided to try his luck with the Dutch.Henry Laurens, of the Continental Congress, had been commissioned as minister to the Netherlands to negotiate a $10 million loan and a Dutch-American treaty. Laurens’s ship, however, was captured by the British. Upon reviewing Laurens’s papers, the British declared war on the Dutch on Dec. 20, 1780. The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War began and would continue through 1784.

Over the course of the next year, Adams worked toward a treaty. It was during this week in history, on April 19, 1782, that The Hague accepted Adams’s credentials as minister, formally recognizing America as an independent state and Adams as the American ambassador. Subsequently, the house in which Adams resided became the first U.S. Embassy.

Not only did Adams become the first ambassador to the Netherlands on April 19, he became the first American ambassador to any country. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the Netherlands and America was signed on Oct. 8, 1782.

Upon recognition of the American nation, the Netherlands became the second nation to do so after France. The relationship between the United States and the Netherlands is arguably the most stable and cooperative in American history with more than 200 years of continued diplomatic relationship.