In the previous article of this series, Hercules completed a daunting second task: He slayed a nine-headed water monster called the Hydra. Now, King Eurystheus mandates that he complete a third labor: to capture the Ceryneian Hind, also known as the Arcadian Stag.

How might we view our own Herculean tasks in light of the insight and wisdom Hercules gains from his third labor?

Artemis and the Arcadian Stag

The story of the Arcadian stags starts with the mountain nymph, Taygete, who unintentionally catches Zeus’s eye. At the moment, Taygete, uninterested in Zeus, resists his advances, though they later have a son, Lakedaimon, who becomes Sparta’s king.Artemis, daughter of Zeus and goddess of hunting and virginity, sees Taygete’s plight and helps her hide from Zeus. In gratitude, Taygete inscribes a stag’s golden antlers with a dedication to Artemis. Artemis is pleased by Taygete’s gift and considers the stag sacred.

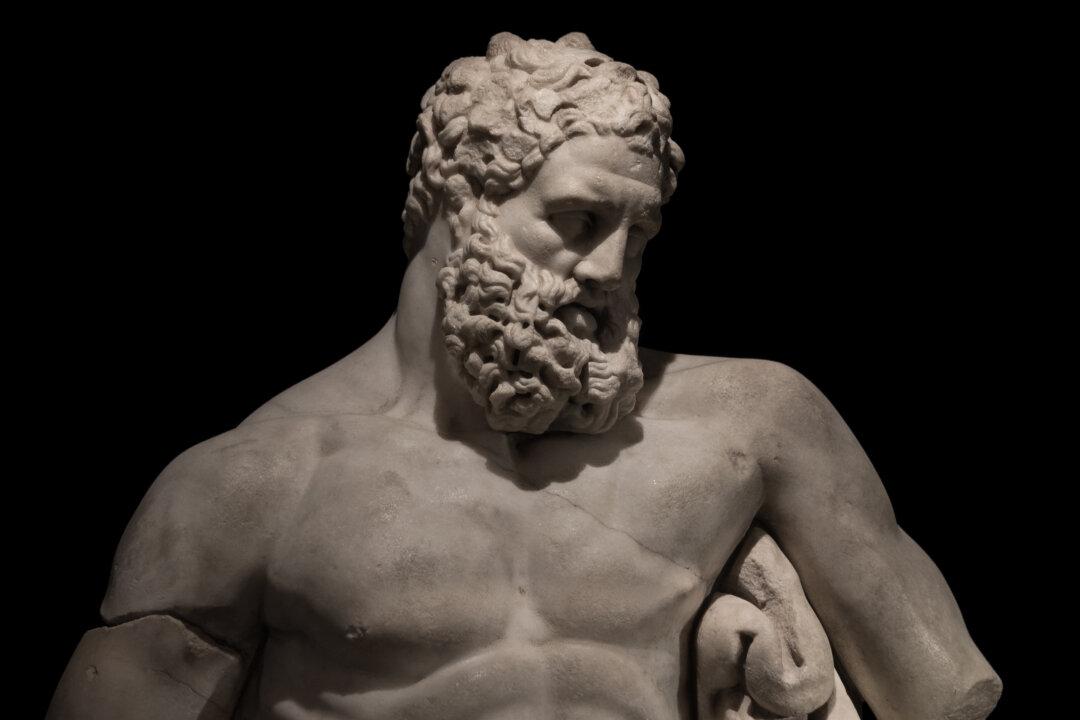

Hercules Captures the Arcadian Stag

King Eurystheus and Hercules both know that Artemis esteems the stag, and no one wants to anger her by disrespecting what she holds sacred. This is what makes this task so difficult. Hercules cannot use his usual strength to accomplish the task. Instead, he must be careful to do as little harm as possible to the revered creature.Hercules pursues it for a year before it tires. He’s still too slow to catch it, so he waits for it to stop as it attempts to cross a river. Taking advantage of this opportunity, Hercules shoots it with an arrow, slightly wounding it. He hoists the injured animal on his shoulder and carries it back to the king.

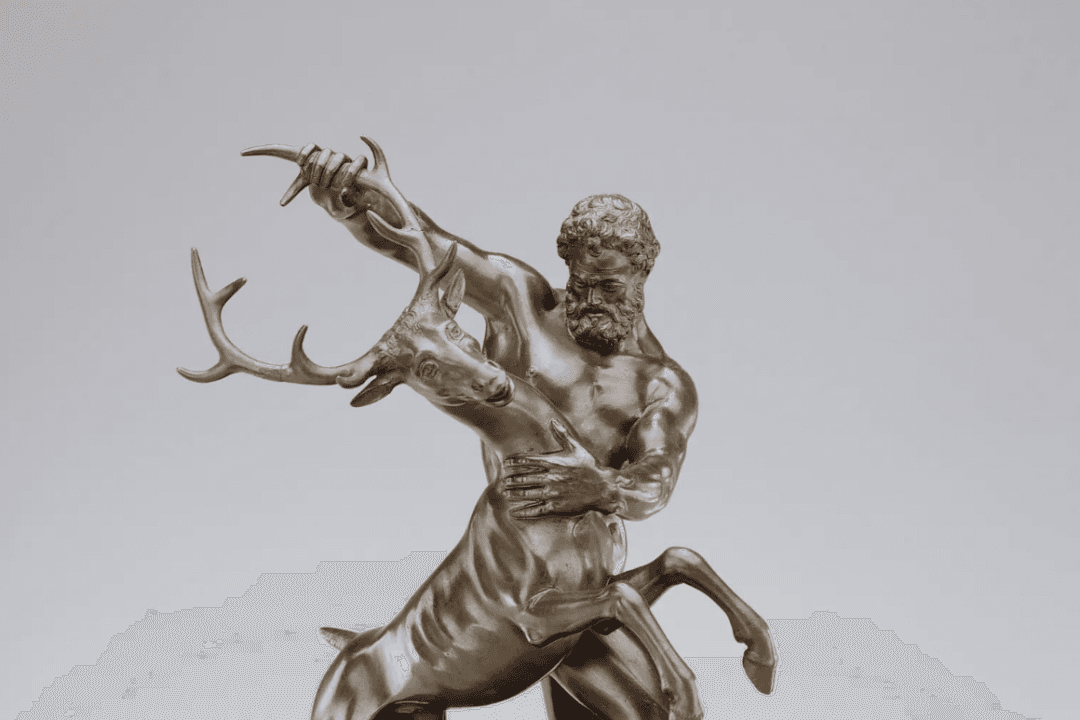

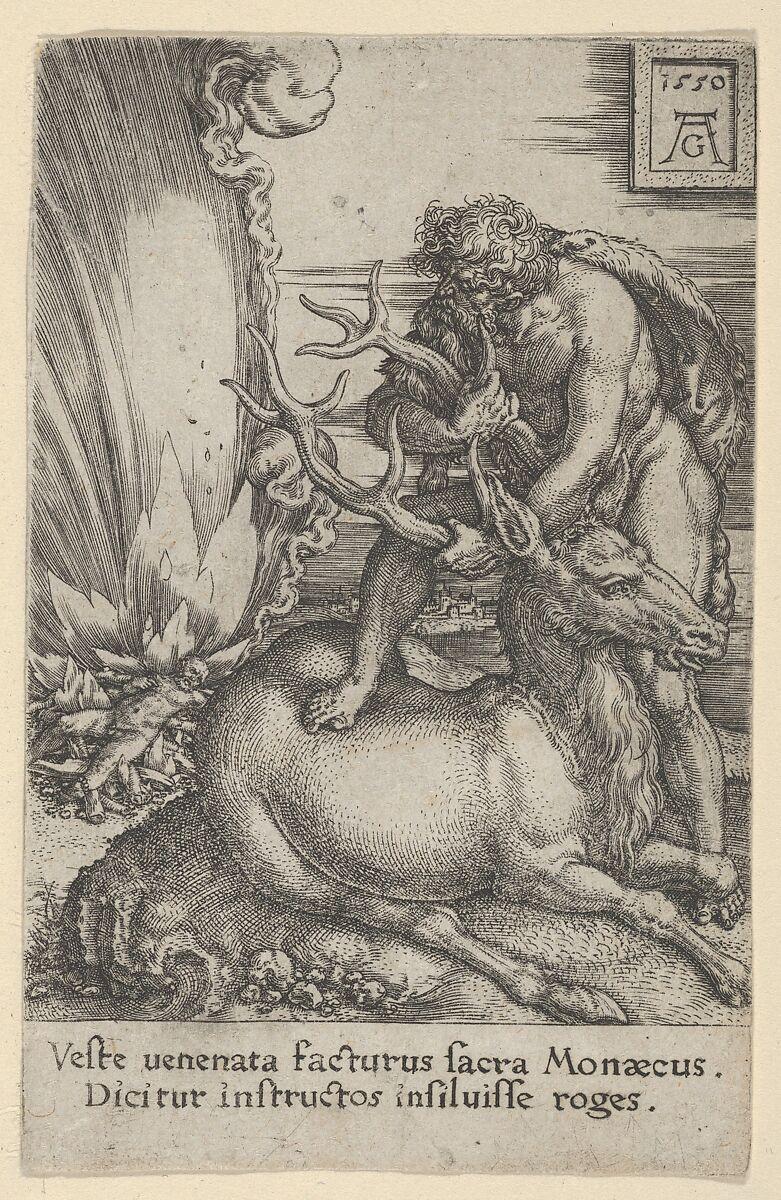

Works of art, such as a bronze sculpture by Antonio Susini and an etching by Heinrich Aldegrever, show the stag without an arrow wound. Instead, we see Hercules grabbing the animal’s antlers as he tries to subdue it. Some versions of the story have him breaking one of the antlers, which he uses later.

On his way to the king, however, Hercules comes across Artemis and her brother, the god Apollo. Seeing that her beloved sacred stag is wounded, Artemis accuses him of trying to kill it. Apollo echoes his sister’s sentiments, and they demand that Hercules return the sacred animal to Artemis.

Hercules has invoked the wrath of two gods, yet this was never his intention. He tells them the full story: This is the will of Hera, Zeus’s wife, who demands that he do King Eurystheus’s bidding. Hercules is merely following a fate for which he cannot be judged, and these tasks are really the King’s desires. Hearing this, Artemis and Apollo pity Hercules and allow him to bring the live stag to King Eurystheus and complete his task.

Great Patience and Gratitude

Hercules demonstrated patience and persistence in capturing the Arcadian stag. He followed it for a year and, along the way, waited for an opportunity to capture it with as little harm as possible.Yet, was he patient enough? I imagine there was a point when Hercules thought: I can shoot this animal and end this now, or I can try to catch it with my hands and end up following it for another year.

Imagine chipping away at the same task for a year and yet seemingly making little progress. When the opportunity to advance finally arrives, many of us would do almost anything to complete the task and move on with our lives. However, is this the best way to do it?

For many, the answer is a resounding yes, and this may be true for most of our tasks. But what about tasks that have a divine element to them? What about those tasks that deal with our spirit’s virtue or our love and gratitude to God?

On the surface, Hercules is chasing a deer around. But here, Hercules’s real task is to capture what the Arcadian stag represents: gratitude for the divine. Capturing a symbol of gratitude for the divine is not merely an outward task, but something that happens internally. Truly accomplishing this, in spirit, heart, and mind, takes persistence and patience. It’s one thing to say “I’m thankful to God!” It’s another to live it, breathe it, and feel it in every moment. That takes real effort.

Hercules is on a journey to reach this gratitude, but he lacks patience. The gratitude he hoists on his shoulders is offensive to the gods because it’s desecrated by his own shortcomings. Yet despite his shortcomings, the gods forgive him when he confesses the whole truth.

How sincere and pure are our intentions and efforts to complete our tasks? Do we make rash decisions because of our impatience? Do our completed tasks symbolize our gratitude to God? Do we open the whole truth of our story up to divine grace despite the difficulties we face?

The previous article in the series shows how Hercules accomplished his second labor, defeating the Hydra.