From Community to Battlefield

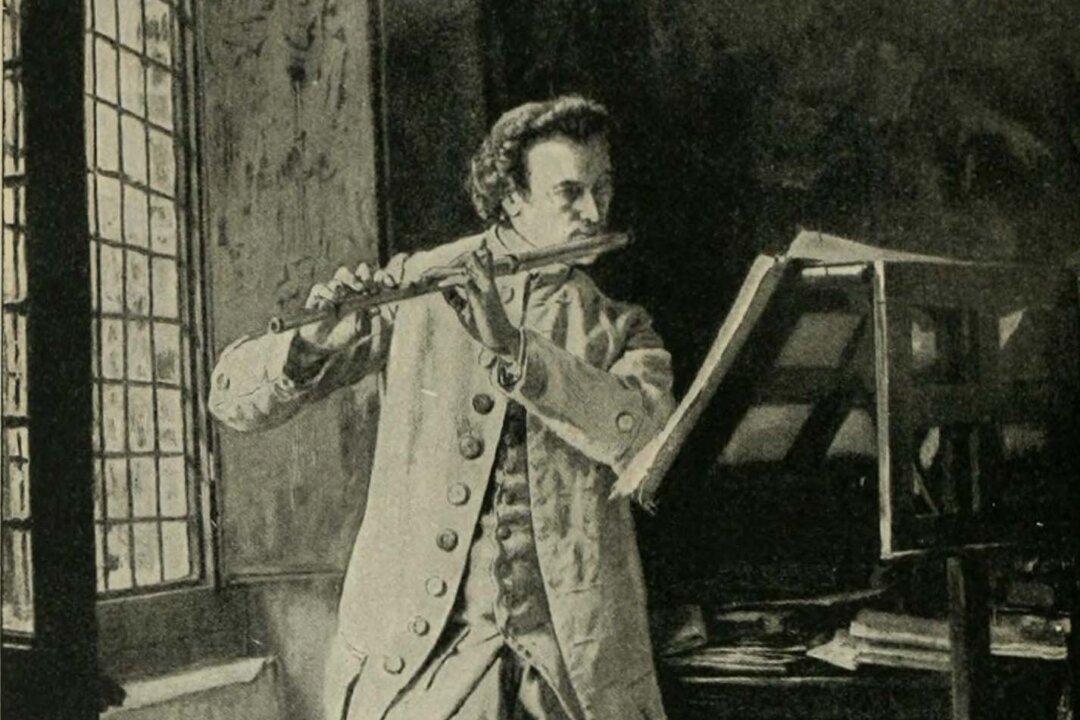

The fife’s origins can be traced back to Europe’s Medieval times. The woodwind instrument borrows its name from the German word “pfeife,” or “pipe,” due to its long, slender body. Europeans traveling to British American colonies brought along the fife instrument, and during the 1700s it became one of the colonists’ favorite instruments. It was so highly favored, it even surpassed the violin and piano in importance.

It could be heard throughout communities in what would become Appalachian America, and the Northern colonies.

Melody as Military Strategy

Fife players, or “fifers,” served many important roles during the Revolutionary War. George Washington, the commander of the Continental Army and future first president of the United States of America, recognized music’s importance and used it in several different ways while fighting British soldiers.

Fifers were often paired with drummers, and these musicians marched and lived among the trained soldiers fighting on the frontlines of the battlefield. Though they did not participate in combat, musicians were considered to be foot soldiers, and earned the respect of those in their regiments due to the key role they played in military strategies.

The fife’s loud, high-pitched tone made it an ideal choice for communication during battle. Amid musket fires, fifers would play various melodies that could be heard by their fellow soldiers over the noise. These various, short melodies told them what direction to continue in, when a cease-fire was being initiated, if a medic was needed, and even when to reload their weapons.

When at camp, fifers’ melodies acted as wake-up calls to soldiers. They also signaled when dinner was ready, or when it was time for chores to be completed. During downtime, fifers played songs from home that soldiers could bond over, boosting camp morale.

Graduating to Drummer

While drummers were often older and more physically fit, fifers tended to be smaller in stature with a wider age range. The average age for a fife musician during the Revolutionary War was 17. However, documentation shows several boys were signed up to be fifers as young as 10 years old. Sometimes, boys would enlist with the help of their fathers.

Some boys who spent years in the military would choose to become a drummer after outgrowing the much smaller wooden instrument.

Soldiers who were both musically gifted and highly capable during battle were promoted to Fife Major or Drum Major, and acted as mentors for the younger musician recruits learning the ropes.

One Fife Major in particular, John McElroy of Pennsylvania’s 11th Regiment, was honored with the title in 1780 after serving as a soldier for several years and suffering injuries while fighting. Even after the war, he was still so attached to his instrument he stated in official papers, “I have my old Fife and knapsack yet.”

Facing Unique Obstacles

Continental Army musicians wore uniforms that differed from their regiments. This helped tell those on opposing sides they were not an individual threat to them. Despite this added protection, musicians faced their own unique obstacles while serving their country.

Long campaigns meant fifers had to play for hours. Sometimes, they played so furiously to communicate across the battlefield that they needed medical attention afterwards. Longtime fifer Samuel Dewees continued serving the military after the Revolutionary War was over. It was during the tax revolt of 1799, Fries’s Rebellion, when he was tested immensely, having to play his instrument over “two or three days.”

A Natural Genius for Music

Fifers and their fellow musicians were so vital to war efforts that when the Continental Army experienced a shortage due to dwindling recruits, those in charge of regiments wrote to military officials who worked directly with George Washington stating their concerns.The Sound of The Fife Continues

As military communications improved, the role of the fifer was reduced. With the invention of technology like radio communication, battlefield musicians became a thing of the past.

Despite the fife no longer serving as an important military tool, its melodies can still be heard in contemporary times. Genres like Celtic folk music and Caribbean music still make use of its sounds from time to time.